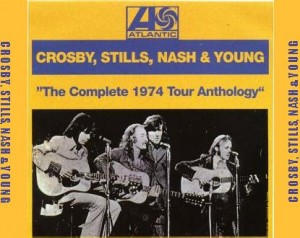

Two friends and the illegally recorded music they both loved. First posted in January 2014, re-posted to coincide with today’s release of CSNY 1974, and especially, the first official release of the Neil Young song “Traces.”

by Tom Casciato

My friend Chris and I went through high school together in Portland in the ‘70s as huge Neil Young fans. In the summer of 2011, when Chris was in the hospital in Seattle being treated for a brain tumor, I found myself going through my extensive collection of Neil Young bootlegs before flying out to see him from New York. I wanted some choice stuff to load onto my iPhone for us to listen to together, as we had in the old days. I didn’t know what kind of shape I’d find him in, and I wanted to pick the perfect music. I chose a boot of a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young concert that he and I had seen together as teenagers.

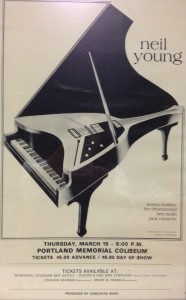

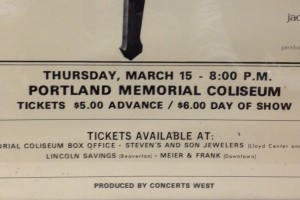

Some background: I first became obsessed with bootleg records – illicitly recorded concerts that, in the days before digital downloads, were released on LPs and later CDs — since shortly after I saw my first Neil Young concert, at Portland’s Memorial Coliseum in1973. I had gone expecting the sweet, familiar sounds and songs of After The Goldrush, and the laid back vibe of Harvest. What I got instead was the kind of raw, apprehensive performance that this particularly tour would later be famous for. The show didn’t start till the opening act, Linda Ronstadt, came on at about 10 pm. When Neil finally hit the stage at around 11, he looked and sounded, well, scraggly. His set – with his backing band, the Stray Gators, and special guest David Crosby — was short.

And I was junkie-hooked on the whole thing. I couldn’t get that music, that band, and especially those new numbers — which I ached to hear again — out of my mind. I had gone home and tried to reconstruct the show from memory, writing down the set list and shards of lyrics, providing my own titles for some of the ones I was unfamiliar with. I thought about that concert so hard and so often that memories of it exist in my mind like video on a hard drive.

But memory wasn’t enough. In fact memory was a kind of pain: it only reminded me of what I didn’t have. I wanted to own that sound. Hell, I wanted to own the night. But that was impossible. So I thought.

It was shortly afterward, at a little underground record store in Portland called D’jango, that I discovered bootleg records. Ostensibly, D’jango dealt in used LPs, and it certainly had thousands of them for sale. But mixed in among the myriad groove-worn copies of Tea For The Tillerman and All Things Must Pass, a coffee-stained Tapestry here, a roach-singed Eat A Peach there, were peculiar LPs that were plastic-wrapped and clearly new but just as clearly not quite legitimate.  The artwork consisted of odd drawings or amateurishly reproduced photos in sickly, washed-out colors. When you tore the plastic off you realized it was all done on a cheap piece of paper that wasn’t even glued to the album cover.

The artwork consisted of odd drawings or amateurishly reproduced photos in sickly, washed-out colors. When you tore the plastic off you realized it was all done on a cheap piece of paper that wasn’t even glued to the album cover.

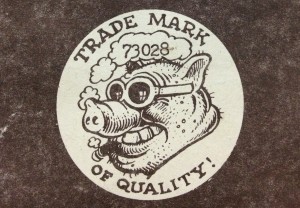

There was also the weirdo creativity of the bootleggers themselves. They had wild names for their companies (one was The Amazing Kornyfone Record Label), and funny, punny names among the credits. (I recall one LP having been produced by an “Arthur Gnuvo.”) There were ludicrous logos (like the one of a conniving, grizzled pig chomping a cigar and haloed by the words “Trade Mark of Quality”) and sly references to the illegality of the whole endeavor, though you had to read very carefully to get the joke (“©1973 All Rights Reversed”).

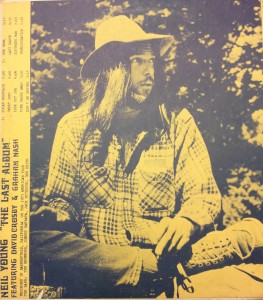

I learned quickly that not every artist was worthy of a bootlegger’s time. (Nobody, apparently, wanted to hear a crappy audience recording of a Neil Diamond concert.) But you could always find something new from Dylan, the Stones, the Who, or Neil Young. And like me coming up with titles for songs I didn’t know, the bootleggers came up with titles for albums they didn’t own. Coming Home, I’m Happy That Y’all Came Down, The Last Album – these were all Neil Young records that Neil Young had never intended would exist. Depending on the recording, the mix would be sometimes awful, with some instruments or vocals way too loud, others nearly inaudible. It was all cheap tawdry, and thrilling. Here was a way to own what couldn’t be owned.

I learned quickly that not every artist was worthy of a bootlegger’s time. (Nobody, apparently, wanted to hear a crappy audience recording of a Neil Diamond concert.) But you could always find something new from Dylan, the Stones, the Who, or Neil Young. And like me coming up with titles for songs I didn’t know, the bootleggers came up with titles for albums they didn’t own. Coming Home, I’m Happy That Y’all Came Down, The Last Album – these were all Neil Young records that Neil Young had never intended would exist. Depending on the recording, the mix would be sometimes awful, with some instruments or vocals way too loud, others nearly inaudible. It was all cheap tawdry, and thrilling. Here was a way to own what couldn’t be owned.

The Last Album was a particular favorite of mine. Recorded in Bakersfield just a few nights before I had seen Neil, it included an extremely rare performance of a song called “Sweet Joni,” which I assumed to have been written about Joni Mitchell. The words to “Sweet Joni” didn’t scan, only sort of rhymed, and made no discernible sense to me:

Sweet Joni

From Saskatoon

Here’s a ring for your finger

It’s shines like the sun

But it feels like the moon.

On top of the eccentric lyrics, Neil sang some of the song hoarse, some of it flat, pretty much  the rest of it hoarse and flat. But this wasn’t music appreciation class; it was paleontology! I imagine I got the same thrill someone gets digging a 50-million year old fossil out of a rock formation in Wyoming. “Sweet Joni” was my primeval fish, my Holy Grail, my smell of napalm in the morning. It was a secret that only we who loved bootlegs knew.

the rest of it hoarse and flat. But this wasn’t music appreciation class; it was paleontology! I imagine I got the same thrill someone gets digging a 50-million year old fossil out of a rock formation in Wyoming. “Sweet Joni” was my primeval fish, my Holy Grail, my smell of napalm in the morning. It was a secret that only we who loved bootlegs knew.

Nowadays, of course, there are no more secrets. You can hear pretty much anything you want. “Sweet Joni,” like a lot of unreleased songs by major artists, is streaming on YouTube, and that’s just the tip of it. Websites featuring unofficially released concerts abound. There’s one call called Sugarmegs where you can download from a database of over seventy thousand bootlegged concerts, including hundreds involving Neil Young.

But that’s now; this was then. Bootlegs had allowed me to conquer memory (even if it was memory had by some people in Bakersfield), to possess evenings and events that, impossibly, had managed to not slip silently into history. With Neil Young boots as my holy scripture I became a proselytizer, a baptizer, and one of my first disciples was my friend Chris.

Chris and I were unlikely buddies. I was a guitar player; he was a football player. I made it through high school without taking physics, chemistry, or calculus (our curriculum having fallen right in the sweet spot of ‘70s progressive education). He aced courses like those, and wanted to become a doctor, like his father. If you had seen us back then at a concert, I’d have been swaying back and forth to the music listening so intently to the lyrics that by the third chorus I’d be singing along to a song I’d never heard before. Chris was attentive too, but reserved, almost arrhythmic. He wouldn’t have been singing because he never pretended he could carry a tune. But he loved the music as much as I did, and it affected him as deeply.

We began hanging out when we were 15, listening to Neil and his compatriots, exchanging ideas about everything from women (which we knew nothing about), to the bitter politics of those late Richard Nixon years (which we knew slightly more about), to the anesthetic effects of cocaine (which he knew a lot about, not because he used cocaine, but because he was planning to grow up to use anesthesia.)

One of our biggest adventures together happened in July of 1974, when he and I and our friend Mike took a train from Portland up to Seattle to see the opening show of the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young reunion tour. Going out of town by ourselves was a big deal on its own. And when our heroes took the stage, it became the night of our lives. They played close to a four hour show, 40 songs strong, and we stood the whole time, not quite able to believe we were in the same room with our idols. Chris and I exchanged knowing smiles when the music got political, first with Graham Nash’s sly jab at the Watergate conspirators, “Grave Concern,” then with Neil Young’s already classic indictment of Nixon, “Ohio.” Throughout the night, he was as usual, more reserved than I was. But he was ecstatically reserved.

Even as I experienced it, I was bent on committing the performance to memory, and this time I had thought ahead. I brought a pen and paper to write down all the songs, again providing my own titles when necessary. At the end of the night my list included a slew of new Neil Young tunes, including “Long May You Run” “Revolution Blues,” and “Human Highway.”

The show didn’t end till after 1:30 in the morning, at which time our escapade continued, as we hitched a ride with some strangers to sleep on the floor of some friends of Chris’s parents on Bellevue Island. The next morning the very kind mom of the house made us waffles with strawberries and whipped cream.

It would be some 20 years before I found a bootleg of that show in a little CD store in Hoboken. (This time I had really hit the jackpot: a bootleg of an incredible show that I had been to myself!) And it was another decade and a half before I downloaded it onto my iPhone to bring out to Seattle to see Chris.

After that show in ’74, there were a couple more years of more hanging out, more going to concerts, more growing up. Then after high school, Chris and I went our separate ways, each to college, then he to medical school, I to New York.

From then on we saw each other infrequently. My memories of him are sporadic but specific: Chris in 1987 in a pressed shirt with a tie, walking down the hall of the San Francisco hospital where he was doing his residency, a stethoscope casually wrapped around his shoulders — the high school kid replaced by a physician. Chris standing outside the church in Portland where I was the best man at his wedding (the marriage would end in divorce); Chris next to me watching Tino Martinez hit three home runs at a Mariners-Yankees game in ‘97 at the Kingdome in Seattle, where he had gone to work as an anesthesiologist and research scientist; Chris and his girlfriend Elizabeth coming to meet me in Portland a decade later for my father’s 90th birthday dinner.

How many times did we see each other in 35 years? Not many. Did it matter to either of us? No. Our friendship wasn’t based on frequency. It was based on availability. I knew he was always there for me, he knew the same of me for him. And we both loved Neil Young. That was pretty much it. The last time I saw him healthy was again at a Mariners game in Seattle, in the fall of 2010. It wasn’t long afterward that he called me with a request: was my dad – a retired judge – still performing wedding ceremonies? Chris and Elizabeth were going to get married. I’m afraid not Chris, I said, the old guy is 93 — though if he’d do it for anyone, you know he’d do it for you. And hey, it’s so great that you’re getting hitched!

There’s something else I have to tell you, he said. I have a brain tumor.

I flew out to Seattle for a weekend to see Chris in June of 2011. I couldn’t be sure how sick he would be when I got there, or how lucid. What I found is what I suppose everyone finds when visiting someone who is being taken by brain cancer, a person mightily diminished, at first close to unrecognizable. He was staying at a hospital rehab facility, gaunt, and hairless of course, suffering the scourges of both his disease and its treatment.

The first day I was there, Elizabeth, said, “Chris, Tom is here. He came all the way from New York. Can you say hi to Tom?” It pained me when he didn’t respond. He was just getting over a bout of pneumonia, and was being fed through a tube in his stomach. He’d been through weeks of proton therapy in Pennsylvania, and now was being treated with Avastin, a last-resort drug for brain cancer, meant to prolong – but not save – the patient’s life. I made a lame joke about how finally he had less hair than I did, that I had been waiting for this day for years. His lips maybe curled into a smile, or maybe didn’t. His eyes were glassy, and made no contact with mine. He was able though, with the aid of a physical therapist and a walker, to manage to walk 120 feet down the hall outside his room. A sign of life.

A few days earlier, knowing I’d be alone in Seattle on a Saturday night with nothing to do, I had bought what I figure was the last of some 62,000 tickets to see U2 at Seattle’s football stadium. Music as medication on a sad, sad night.

The show had some great theatrical moments, including a striking bit at the end involving the Burmese political prisoner, Aung San Suu Kyi. I had seen U2 a couple years before, and toward the end of the show Bono went into a rap about the democracy movement in Burma, and called for Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest. Now, he was back with the Burmese rap again, but this time around, Suu Kyi having since been released, appeared on the giant video screen, addressing the crowd, extolling democracy. I couldn’t help thinking it was a politics-and-music moment Chris would have liked.

The next day, back in the rehab facility, Chris was able to walk even further. He even went a little faster, though his “fast” was excruciatingly slow.

My sister had come up from Portland for the day, and for a time she and Chris and Elizabeth and I hung out in a sitting room down the hall from Chris’s bed. At one point Elizabeth asked me how the U2 concert was, and I began to give a blow-by-blow account. When I got to the part about Aung San Suu Kyi, I noticed that Chris was looking at me, suddenly rapt, with a glassy smile.

Did he know who I was?

I pounced. I asked him, Chris, do you know the last time I saw a concert in Seattle? It was when we were 16, and you and me and Mike took a train up here from Portland to see the opening night of the CSNY reunion tour.  The show got out after 1:30 in the morning, and we didn’t know where the hell we were, and we hitched a ride with some people we didn’t know out to Bellevue Island, where we stayed with some friends of your parents, and we slept on their living room floor, and the next morning we woke up to this very nice woman making us waffles with whipped cream and strawberries.

The show got out after 1:30 in the morning, and we didn’t know where the hell we were, and we hitched a ride with some people we didn’t know out to Bellevue Island, where we stayed with some friends of your parents, and we slept on their living room floor, and the next morning we woke up to this very nice woman making us waffles with whipped cream and strawberries.

The same glassy smile.

Elizabeth said, “Chris, do you remember that? Do you remember that concert? Do you remember staying with your parents’ friends? Who were those friends, Chris? Can you tell me their names? Chris, who were your parents’ friends?”

A Harold Pinter pause. Then he said, “The Thompsons.”

Pure joy! And now I pulled out my secret weapon.

“Chris, do you know what I have on my iPhone? I have a bootleg of that show, that one we saw in 1974 of Crosby, Stills Nash and Young playing in Seattle. Do you want to hear some?”

A raspy, feeble “Yes.”

“Here’s ‘Ohio,” I said, as his wife put my ear buds in his ears. The smile got bigger. Then I played him “Grave Concern,” then Crosby, Stills and Nash doing “Suite: Judy Blues Eyes” as a trio. Then I slipped in that slight little Neil Young song, “Traces.”

“Here’s one you can only hear on a boot,” I said.

As Chris listened through the ear buds, I thought about the lyrics, which are as opaque as those of “Sweet Joni.” I’ve heard the song a thousand times and I still don’t know what it’s about, except that I know it’s got something to do with leaving. Leaving a place, leaving someone, maybe leaving this world. Backed by sunny chords that suddenly go dark at the end of the chorus, Young sings

None of the neighbors remember names

They only see the faces

With destination still unnamed

It’s hard to leave the traces

For someone to follow

Chris listened and smiled, huge. I told him when I got home to New York I was going to burn him a CD of the whole show. Would he like that? A strangled “yes.” For a few minutes I had my friend back, if not whole, then wholly involved in the music we had both loved since we were teenagers, would love as long as we lived.

Chris lived not too much longer.

I flew out to see Chris one more time before he passed away, but I’ve blocked out most of the trip; I only recall that he was far beyond knowing I was there. I still think about that previous visit, though, especially when I go see Neil Young, which I’ll be doing next week. The show is at Carnegie Hall, and I’m sure performances from it it will quickly appear on YouTube. And no doubt someone will be taping the whole concert, and it will soon be available on Sugarmegs. But I don’t suppose I’ll ever listen to it, any more than I’ve ever listened again to that Seattle bootleg since the last time I heard it with Chris. I’m past the point of thinking I can own what I remember.