Two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Graham Nash has hits aplenty spanning his nearly six-decade career. But the 77-year-old singer-songwriter recently chose to perform a special run of shows featuring his lesser-known first two solo albums in their entirety, which together describe a crucial chapter in his personal and artistic life. Tom Casciato recently spoke to Nash to learn more.

Author Archives: Borrowed Tune

Carlos Santana 50 years after Woodstock: “Kumbaya will kick your ass”

As we near the 50th anniversary of Woodstock, Carlos Santana speaks with Tom Casciato about the smell of his childhood violin, the way Otis Rush influenced him, his hallucinogenic Woodstock performance, and how “Kumbaya will kick your ass from here to eternity.”

Tom Casciato’s and Nils Lofgren on PBS NewsHour Weekend

I recently interviewed Nils during his 50th anniversary tour on Bruce Springsteen’s home court at the Stone Pony in Asbury Park, NJ, and again at NYC’s City Winery. Here’s the story.

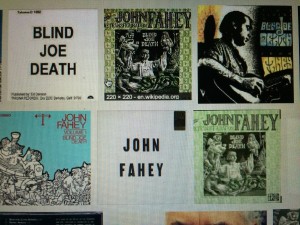

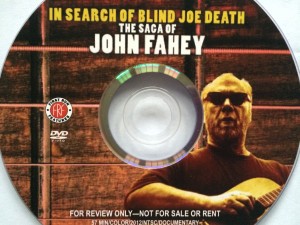

Blind Joe Death: Found

A legendary guitarist and his story finely — and finally — told …

by Tom Casciato

I saw John Fahey perform only once, at an auditorium at Stanford in, I think, the very early ‘80s. Fahey was a guitarist’s guitarist, and his style of steel-string fingerpicking had a devoted following in Palo Alto, William Ackerman’s local Windham Hill label having recently boosted the genre’s visibility and popularity. The crowd was poised for greatness. Fahey, though, was terrible, and he was drunk. He looked lost in the very place I figured he should have been at home – the stage – and I left the show sad and puzzled.

Fahey was a giant of the solo guitar genre. His first LP Blind Joe Death, was released in 1959 when he was just 20, and though only a hundred copies were pressed originally, it has become a classic. Another landmark record, his 1968 album, The New Possibility, was a collection of impossibly beautiful renditions of traditional Christmas songs that a person – for example, me – might have thought long since hackneyed. But by the time I saw him, Fahey’s position had been usurped by younger players — first Leo Kottke, then, in quick succession, Ackerman and Alex DeGrassi. One after the other they surpassed Fahey in technique and/or speed, and each brought enough soulfulness to the party so as to make Fahey seem pretty close to anachronistic. But if they were the Wilt, Kareem and Shaq of the genre, Fahey was the George Mikan, the one who – as Warren Zevon once said of Bob Dylan — invented the job.

But by the time I saw him, Fahey’s position had been usurped by younger players — first Leo Kottke, then, in quick succession, Ackerman and Alex DeGrassi. One after the other they surpassed Fahey in technique and/or speed, and each brought enough soulfulness to the party so as to make Fahey seem pretty close to anachronistic. But if they were the Wilt, Kareem and Shaq of the genre, Fahey was the George Mikan, the one who – as Warren Zevon once said of Bob Dylan — invented the job.

His playing walked an elegant line. It was gritty enough to a lay a claim to the blues, and never so earnest as to be dismissed as “folkie.” His songs and structures were formal but not pinched. It was music that had connections to the Delta, to ragtime, to Europe and even India, but it couldn’t claim those places as its own. Mostly, it was American music, borrowing, stealing, rearranging and ultimately creating something new. And unlike most of what I grew up listening to in the early 1970s, during the heyday of the singer/songwriter, it had no words.

Though I listened to music (on my crappy stereo) intently as a kid, taking in every voicing of a chord, every slur of a note, every accent of a snare, I was literal-minded enough to take my narrative purely from the lyrics. It was the Beatles, and John Lennon in particular, who first hooked me, with story-songs like “In My Life” and “Norwegian Wood.” I believed him when he said he needed “Help!” When he said of himself “I’m A Loser” I believed him. I knew what his songs were about, because he told me himself.

I didn’t know what Fahey’s songs were “about,” though as someone who devoured album credits as eagerly as I did lyrics, I did grab onto the strangeness of the language I found on his LPs. First, there was that name “Blind Joe Death” – I later learned it was an alias he sometimes used, and now I think of it as a tip of the hat to his bluesman influences (Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ivory Joe Hunter) or perhaps a bit of knowing, Lettermanesque humor decades before David Letterman invented it. (Fahey was more than capable of sidelong wit: one of his early compositions is called “Stomping Tonight On The Pennsylvania/Alabama Border,” comically obliterating the distance between the two states long before the famous James Carville quote did the same.) Back then, I couldn’t figure out what he could possibly be up to.

Then there was the evocative word “Takoma.” That was the name of the record label he owned and recorded on, named for the Maryland neighborhood where he grew up, Takoma Park. I know that now. But when I was listening to Fahey as a kid in Portland, with little knowledge of the country anywhere east of, say, Reno, “Takoma” was a mysterious, somewhat sinister word — a darkened spelling of “Tacoma” perhaps, as “Amerika” was to America? I couldn’t be sure. The music, too, had a mystery to it, as well as, at least for me, a hard-to-grasp kind of pain that unlike, say, Lennon’s, went wholly un-illuminated by lyrics. Whether on a deceptively simple, folk-ish track like “Sligo River Blues,” or the bluesy but deliberate “Some Summer Day,” Fahey played like someone for whom the music was much more than pretty.

I now know much more about what John Fahey was trying to get across having seen James Cullingham’s fine 2013 documentary, In Search Of Blind Joe Death: The Saga Of John Fahey. It’s a love letter of a movie that gives the master his due, from filmmakers, fans, and fellow musicians (Pete Townsend, Stefan Grossman, Chris Funk of the Decembrists and Calexico’s Joey Burns, among them) who really get what Fahey’s music was about.

The film makes Fahey the person – rather than Fahey the guitarist — appear to have been mostly unknowable. The comments unrelated to his playing are not particularly revealing. But throughout many choice, vintage clips, Fahey manages to make himself known nonetheless. Whether blithely knocking cigarette ash into the soundhole of his Hawaiian guitar (though a solo acoustic player, “the guy was truly punk rock,” Funk observes astutely) or admitting to a violent urge (“I think the guitar helped keep me from going nuts … I could sit around and bang on the guitar instead of banging on somebody else.”), Fahey nearly always displays an edge befitting his beautiful-but-not-sweet style.

But throughout many choice, vintage clips, Fahey manages to make himself known nonetheless. Whether blithely knocking cigarette ash into the soundhole of his Hawaiian guitar (though a solo acoustic player, “the guy was truly punk rock,” Funk observes astutely) or admitting to a violent urge (“I think the guitar helped keep me from going nuts … I could sit around and bang on the guitar instead of banging on somebody else.”), Fahey nearly always displays an edge befitting his beautiful-but-not-sweet style.

The film has more to recommend it as well, including great stock footage of Fahey in performance at various stages of his life. But you also witness him slipping, disheveled, deeply into alcoholism when he moves, in the early ‘80s to Salem, Oregon, an unlikely home for an artist who Pete Townsend compares to William Burroughs and Charles Bukowski. (There’s also – a personal pleasure for me — some vintage 8 mm stuff of Portland, including shots of the classic Hollywood Theater and the kitschy Pagoda restaurant.) Health crises and, eventually, poverty would follow, until he died in 2001.

But it wasn’t until about three quarters through that In Search Of Blind Joe Death supplied what for me are the lyrics of his music, the words that I felt but never heard all those years ago. I won’t spoil it with a direct quote – if you like his music you should see the film — but suffice to say that Fahey sources his pain in abuse he suffered as a child.

His telling is brief (and the film handles it with taste), but hearing it was just enough to send me back to that night, decades ago, when I saw the sorry legend embarrass himself in front of a crowd who had no doubt come to praise and even worship him. It didn’t make the music sound any better in retrospect. But now, decades later, I think I understand what his songs were about.

Or maybe I don’t. I’ve no doubt that the experience of an artist like Fahey shows up in his art, but exactly how remains a mystery — no matter how much I want to pour my interpretation of his feelings into his work. But after seeing In Search of Blind Joe Death, there is one thing I do understand, something that takes me back to that John Fahey show I went to all those years ago. Around the same time, I went to hear Hunter S. Thompson speak at the same auditorium. He, too, was drunk (or stoned, or both, or whatever). Far worse, he was a bore. Fahey, all messed up on that same stage, seemed something else: a tragedy. Now I know why.

Here are a few Fahey favorites, including the tunes mentioned above …

Of Brains And Boots

Two friends and the illegally recorded music they both loved …

by Tom Casciato

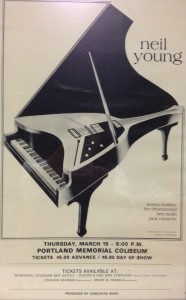

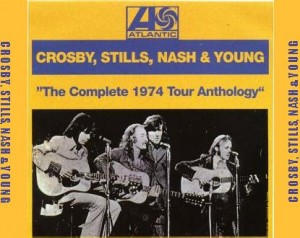

My friend Chris and I went through high school together in Portland in the ‘70s as huge Neil Young fans. In the summer of 2011, when Chris was in the hospital in Seattle being treated for a brain tumor, I found myself going through my extensive collection of Neil Young bootlegs before flying out to see him from New York. I wanted some choice stuff to load onto my iPhone for us to listen to together, as we had in the old days. I didn’t know what kind of shape I’d find him in, and I wanted to pick the perfect music. I chose a boot of a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young concert that he and I had seen together as teenagers.

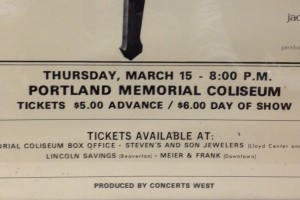

Some background: I first became obsessed with bootleg records – illicitly recorded concerts that, in the days before digital downloads, were released on LPs and later CDs — since shortly after I saw my first Neil Young concert, at Portland’s Memorial Coliseum in1973. I had gone expecting the sweet, familiar sounds and songs of After The Goldrush, and the laid back vibe of Harvest. What I got instead was the kind of raw, apprehensive performance that this particularly tour would later be famous for. The show didn’t start till the opening act, Linda Ronstadt, came on at about 10 pm. When Neil finally hit the stage at around 11, he looked and sounded, well, scraggly. His set – with his backing band, the Stray Gators, and special guest David Crosby — was short.

And I was junkie-hooked on the whole thing. I couldn’t get that music, that band, and especially those new numbers — which I ached to hear again — out of my mind. I had gone home and tried to reconstruct the show from memory, writing down the set list and shards of lyrics, providing my own titles for some of the ones I was unfamiliar with. I thought about that concert so hard and so often that memories of it exist in my mind like video on a hard drive.

But memory wasn’t enough. In fact memory was a kind of pain: it only reminded me of what I didn’t have. I wanted to own that sound. Hell, I wanted to own the night. But that was impossible. So I thought.

It was shortly afterward, at a little underground record store in Portland called D’jango, that I discovered bootleg records. Ostensibly, D’jango dealt in used LPs, and it certainly had thousands of them for sale. But mixed in among the myriad groove-worn copies of Tea For The Tillerman and All Things Must Pass, a coffee-stained Tapestry here, a roach-singed Eat A Peach there, were peculiar LPs that were plastic-wrapped and clearly new but just as clearly not quite legitimate.  The artwork consisted of odd drawings or amateurishly reproduced photos in sickly, washed-out colors. When you tore the plastic off you realized it was all done on a cheap piece of paper that wasn’t even glued to the album cover.

The artwork consisted of odd drawings or amateurishly reproduced photos in sickly, washed-out colors. When you tore the plastic off you realized it was all done on a cheap piece of paper that wasn’t even glued to the album cover.

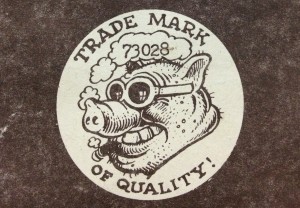

There was also the weirdo creativity of the bootleggers themselves. They had wild names for their companies (one was The Amazing Kornyfone Record Label), and funny, punny names among the credits. (I recall one LP having been produced by an “Arthur Gnuvo.”) There were ludicrous logos (like the one of a conniving, grizzled pig chomping a cigar and haloed by the words “Trade Mark of Quality”) and sly references to the illegality of the whole endeavor, though you had to read very carefully to get the joke (“©1973 All Rights Reversed”).

I learned quickly that not every artist was worthy of a bootlegger’s time. (Nobody, apparently, wanted to hear a crappy audience recording of a Neil Diamond concert.) But you could always find something new from Dylan, the Stones, the Who, or Neil Young. And like me coming up with titles for songs I didn’t know, the bootleggers came up with titles for albums they didn’t own. Coming Home, I’m Happy That Y’all Came Down, The Last Album – these were all Neil Young records that Neil Young had never intended would exist. Depending on the recording, the mix would be sometimes awful, with some instruments or vocals way too loud, others nearly inaudible. It was all cheap tawdry, and thrilling. Here was a way to own what couldn’t be owned.

I learned quickly that not every artist was worthy of a bootlegger’s time. (Nobody, apparently, wanted to hear a crappy audience recording of a Neil Diamond concert.) But you could always find something new from Dylan, the Stones, the Who, or Neil Young. And like me coming up with titles for songs I didn’t know, the bootleggers came up with titles for albums they didn’t own. Coming Home, I’m Happy That Y’all Came Down, The Last Album – these were all Neil Young records that Neil Young had never intended would exist. Depending on the recording, the mix would be sometimes awful, with some instruments or vocals way too loud, others nearly inaudible. It was all cheap tawdry, and thrilling. Here was a way to own what couldn’t be owned.

The Last Album was a particular favorite of mine. Recorded in Bakersfield just a few nights before I had seen Neil, it included an extremely rare performance of a song called “Sweet Joni,” which I assumed to have been written about Joni Mitchell. The words to “Sweet Joni” didn’t scan, only sort of rhymed, and made no discernible sense to me:

Sweet Joni

From Saskatoon

Here’s a ring for your finger

It’s shines like the sun

But it feels like the moon.

On top of the eccentric lyrics, Neil sang some of the song hoarse, some of it flat, pretty much  the rest of it hoarse and flat. But this wasn’t music appreciation class; it was paleontology! I imagine I got the same thrill someone gets digging a 50-million year old fossil out of a rock formation in Wyoming. “Sweet Joni” was my primeval fish, my Holy Grail, my smell of napalm in the morning. It was a secret that only we who loved bootlegs knew.

the rest of it hoarse and flat. But this wasn’t music appreciation class; it was paleontology! I imagine I got the same thrill someone gets digging a 50-million year old fossil out of a rock formation in Wyoming. “Sweet Joni” was my primeval fish, my Holy Grail, my smell of napalm in the morning. It was a secret that only we who loved bootlegs knew.

Nowadays, of course, there are no more secrets. You can hear pretty much anything you want. “Sweet Joni,” like a lot of unreleased songs by major artists, is streaming on YouTube, and that’s just the tip of it. Websites featuring unofficially released concerts abound. There’s one call called Sugarmegs where you can download from a database of over seventy thousand bootlegged concerts, including hundreds involving Neil Young.

But that’s now; this was then. Bootlegs had allowed me to conquer memory (even if it was memory had by some people in Bakersfield), to possess evenings and events that, impossibly, had managed to not slip silently into history. With Neil Young boots as my holy scripture I became a proselytizer, a baptizer, and one of my first disciples was my friend Chris.

Chris and I were unlikely buddies. I was a guitar player; he was a football player. I made it through high school without taking physics, chemistry, or calculus (our curriculum having fallen right in the sweet spot of ‘70s progressive education). He aced courses like those, and wanted to become a doctor, like his father. If you had seen us back then at a concert, I’d have been swaying back and forth to the music listening so intently to the lyrics that by the third chorus I’d be singing along to a song I’d never heard before. Chris was attentive too, but reserved, almost arrhythmic. He wouldn’t have been singing because he never pretended he could carry a tune. But he loved the music as much as I did, and it affected him as deeply.

We began hanging out when we were 15, listening to Neil and his compatriots, exchanging ideas about everything from women (which we knew nothing about), to the bitter politics of those late Richard Nixon years (which we knew slightly more about), to the anesthetic effects of cocaine (which he knew a lot about, not because he used cocaine, but because he was planning to grow up to use anesthesia.)

One of our biggest adventures together happened in July of 1974, when he and I and our friend Mike took a train from Portland up to Seattle to see the opening show of the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young reunion tour. Going out of town by ourselves was a big deal on its own. And when our heroes took the stage, it became the night of our lives. They played close to a four hour show, 40 songs strong, and we stood the whole time, not quite able to believe we were in the same room with our idols. Chris and I exchanged knowing smiles when the music got political, first with Graham Nash’s sly jab at the Watergate conspirators, “Grave Concern,” then with Neil Young’s already classic indictment of Nixon, “Ohio.” Throughout the night, he was as usual, more reserved than I was. But he was ecstatically reserved.

Even as I experienced it, I was bent on committing the performance to memory, and this time I had thought ahead. I brought a pen and paper to write down all the songs, again providing my own titles when necessary. At the end of the night my list included a slew of new Neil Young tunes, including “Long May You Run” “Revolution Blues,” and “Human Highway.”

The show didn’t end till after 1:30 in the morning, at which time our escapade continued, as we hitched a ride with some strangers to sleep on the floor of some friends of Chris’s parents on Bellevue Island. The next morning the very kind mom of the house made us waffles with strawberries and whipped cream.

It would be some 20 years before I found a bootleg of that show in a little CD store in Hoboken. (This time I had really hit the jackpot: a bootleg of an incredible show that I had been to myself!) And it was another decade and a half before I downloaded it onto my iPhone to bring out to Seattle to see Chris.

After that show in ’74, there were a couple more years of more hanging out, more going to concerts, more growing up. Then after high school, Chris and I went our separate ways, each to college, then he to medical school, I to New York.

From then on we saw each other infrequently. My memories of him are sporadic but specific: Chris in 1987 in a pressed shirt with a tie, walking down the hall of the San Francisco hospital where he was doing his residency, a stethoscope casually wrapped around his shoulders — the high school kid replaced by a physician. Chris standing outside the church in Portland where I was the best man at his wedding (the marriage would end in divorce); Chris next to me watching Tino Martinez hit three home runs at a Mariners-Yankees game in ‘97 at the Kingdome in Seattle, where he had gone to work as an anesthesiologist and research scientist; Chris and his girlfriend Elizabeth coming to meet me in Portland a decade later for my father’s 90th birthday dinner.

How many times did we see each other in 35 years? Not many. Did it matter to either of us? No. Our friendship wasn’t based on frequency. It was based on availability. I knew he was always there for me, he knew the same of me for him. And we both loved Neil Young. That was pretty much it. The last time I saw him healthy was again at a Mariners game in Seattle, in the fall of 2010. It wasn’t long afterward that he called me with a request: was my dad – a retired judge – still performing wedding ceremonies? Chris and Elizabeth were going to get married. I’m afraid not Chris, I said, the old guy is 93 — though if he’d do it for anyone, you know he’d do it for you. And hey, it’s so great that you’re getting hitched!

There’s something else I have to tell you, he said. I have a brain tumor.

I flew out to Seattle for a weekend to see Chris in June of 2011. I couldn’t be sure how sick he would be when I got there, or how lucid. What I found is what I suppose everyone finds when visiting someone who is being taken by brain cancer, a person mightily diminished, at first close to unrecognizable. He was staying at a hospital rehab facility, gaunt, and hairless of course, suffering the scourges of both his disease and its treatment.

The first day I was there, Elizabeth, said, “Chris, Tom is here. He came all the way from New York. Can you say hi to Tom?” It pained me when he didn’t respond. He was just getting over a bout of pneumonia, and was being fed through a tube in his stomach. He’d been through weeks of proton therapy in Pennsylvania, and now was being treated with Avastin, a last-resort drug for brain cancer, meant to prolong – but not save – the patient’s life. I made a lame joke about how finally he had less hair than I did, that I had been waiting for this day for years. His lips maybe curled into a smile, or maybe didn’t. His eyes were glassy, and made no contact with mine. He was able though, with the aid of a physical therapist and a walker, to manage to walk 120 feet down the hall outside his room. A sign of life.

A few days earlier, knowing I’d be alone in Seattle on a Saturday night with nothing to do, I had bought what I figure was the last of some 62,000 tickets to see U2 at Seattle’s football stadium. Music as medication on a sad, sad night.

The show had some great theatrical moments, including a striking bit at the end involving the Burmese political prisoner, Aung San Suu Kyi. I had seen U2 a couple years before, and toward the end of the show Bono went into a rap about the democracy movement in Burma, and called for Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest. Now, he was back with the Burmese rap again, but this time around, Suu Kyi having since been released, appeared on the giant video screen, addressing the crowd, extolling democracy. I couldn’t help thinking it was a politics-and-music moment Chris would have liked.

The next day, back in the rehab facility, Chris was able to walk even further. He even went a little faster, though his “fast” was excruciatingly slow.

My sister had come up from Portland for the day, and for a time she and Chris and Elizabeth and I hung out in a sitting room down the hall from Chris’s bed. At one point Elizabeth asked me how the U2 concert was, and I began to give a blow-by-blow account. When I got to the part about Aung San Suu Kyi, I noticed that Chris was looking at me, suddenly rapt, with a glassy smile.

Did he know who I was?

I pounced. I asked him, Chris, do you know the last time I saw a concert in Seattle? It was when we were 16, and you and me and Mike took a train up here from Portland to see the opening night of the CSNY reunion tour.  The show got out after 1:30 in the morning, and we didn’t know where the hell we were, and we hitched a ride with some people we didn’t know out to Bellevue Island, where we stayed with some friends of your parents, and we slept on their living room floor, and the next morning we woke up to this very nice woman making us waffles with whipped cream and strawberries.

The show got out after 1:30 in the morning, and we didn’t know where the hell we were, and we hitched a ride with some people we didn’t know out to Bellevue Island, where we stayed with some friends of your parents, and we slept on their living room floor, and the next morning we woke up to this very nice woman making us waffles with whipped cream and strawberries.

The same glassy smile.

Elizabeth said, “Chris, do you remember that? Do you remember that concert? Do you remember staying with your parents’ friends? Who were those friends, Chris? Can you tell me their names? Chris, who were your parents’ friends?”

A Harold Pinter pause. Then he said, “The Thompsons.”

Pure joy! And now I pulled out my secret weapon.

“Chris, do you know what I have on my iPhone? I have a bootleg of that show, that one we saw in 1974 of Crosby, Stills Nash and Young playing in Seattle. Do you want to hear some?”

A raspy, feeble “Yes.”

“Here’s ‘Ohio,” I said, as his wife put my ear buds in his ears. The smile got bigger. Then I played him “Grave Concern,” then Crosby, Stills and Nash doing “Suite: Judy Blues Eyes” as a trio. Then I slipped in that slight little Neil Young song, “Traces.”

“Here’s one you can only hear on a boot,” I said.

As Chris listened through the ear buds, I thought about the lyrics, which are as opaque as those of “Sweet Joni.” I’ve heard the song a thousand times and I still don’t know what it’s about, except that I know it’s got something to do with leaving. Leaving a place, leaving someone, maybe leaving this world. Backed by sunny chords that suddenly go dark at the end of the chorus, Young sings

None of the neighbors remember names

They only see the faces

With destination still unnamed

It’s hard to leave the traces

For someone to follow

Chris listened and smiled, huge. I told him when I got home to New York I was going to burn him a CD of the whole show. Would he like that? A strangled “yes.” For a few minutes I had my friend back, if not whole, then wholly involved in the music we had both loved since we were teenagers, would love as long as we lived.

Chris lived not too much longer.

I flew out to see Chris one more time before he passed away, but I’ve blocked out most of the trip; I only recall that he was far beyond knowing I was there. I still think about that previous visit, though, especially when I go see Neil Young, which I’ll be doing next week. The show is at Carnegie Hall, and I’m sure performances from it it will quickly appear on YouTube. And no doubt someone will be taping the whole concert, and it will soon be available on Sugarmegs. But I don’t suppose I’ll ever listen to it, any more than I’ve ever listened again to that Seattle bootleg since the last time I heard it with Chris. I’m past the point of thinking I can own what I remember.

Loving Joni Mitchell: You Don’t Have To Be Gay

An appreciation of JM first published on the PBS Need To Know website in 2011 – given a light edit here

by Tom Casciato

The Oscars are over, last year’s movies are exactly that. But there’s one scene I can’t let go of.

But first, an aside. Hollywood pictures have been milking scenes of actors singing or emoting to pop songs for about three decades now, ever since that too-cute “Big Chill” gang rocked out in the kitchen to “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg,” and — much more amusingly — the incarcerated Eddie Murphy howled “Roxanne” under the headphones in “48 Hours.” There have been countless imitations since, and it’s pretty hard to be charmed or surprised by any of it anymore.

Then along come Annette Bening and Mark Ruffalo, bringing a fresh twist to a tired gimmick in “The Kids Are All Right.” It’s the scene where Bening’s lesbian character and Ruffalo’s straight one psychically bond while singing Joni Mitchell’s lovely “All I Want” as an a cappella duet over dinner. (Meanwhile a perplexed Julianne Moore, whose character has been sleeping with each of them, looks on forlornly, utterly excluded from their vocal hookup.) The scene became significant for me with Bening’s declaration: “You don’t meet too many straight guys who love Joni Mitchell!”

There was a time I was somewhat afraid to say so. Like in high school (mine was of the all-boys variety), when it would have been socially unwise to admit that I found ZZ Top’s “Tush” dull, if not obnoxious, but, hey, have you checked out the way Joni Mitchell uses that Burundian drum ensemble on The Hissing of Summer Lawns?

If you don’t love Joni Mitchell, there’s a good chance you’ve never even heard of The Hissing of Summer Lawns. It was the 1975 followup to the previous year’s Court and Spark, which had been one of the few albums of the era to qualify both as artistic triumph and commercial breakthrough. Hissing was where a lot of people got off the Joni bus. Up till then her albums had managed to define inventive lyrical and musical territory while still containing a healthy enough number of pop-inflected songs like “All I Want” to allow her to sell a bundle of records.

With Hissing that all changed. The aforementioned Burundian drums were found on a song called “The Jungle Line,” by leaps the most melodically challenging track she had ever released. The rest of the album is slightly more accessible but filled with unapologetically ambitious arrangements, sophisticated melodies, knowing feminist lyrics – in other words, nobody’s idea of a hit. Songs like “In France They Kiss on Main Street,” “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow” and “The Boho Dance” weren’t quite pop, weren’t quite jazz, weren’t quite like anything anyone else was doing. And so she was, in many quarters, demeaned for it.

I recall my desire (still strong some three and a half decades later) to defend her honor when Rolling Stone’s Stephen Holden attacked Hissing’s musicality in his review of the album. Among his other charges, he said the synthesizer on the song “Shadows and Light” sounded like “a long solemn fart.”

(An aside: the way I remembered it, Holden had compared Mitchell’s synth sound not to a long solemn fart, but to a “goose fart.” Then I Googled it, and it turns out that “goose fart” – or, to be precise, “geese farting on a muggy day” — was the term guitarist Leo Kottke used to describe the sound of his own singing voice. A further aside: Kottke wasn’t far off. But whether of the goose or the long-and-solemn variety, a fart is still a fart, and I took what I read in that magazine to be fighting words.)

Not, by the way, that the synth on “Shadows and Light” didn’t sound like a fart. (Judge for yourself.) That wasn’t the point. To my mind, Stephen Holden had besmirched Joni’s honor at a time when — to use a hackneyed phrase from those dull, post-Beatles, pre-punk days — she was taking it to the limit while rock stars who weren’t taking it to the limit were becoming jillionaires filling my car speakers with the unambitious likes of “Take It to the Limit.”

I’m thinking, the radio is rife with sonic flatulence, and you want to go picking on Joni Mitchell?

(Another aside: Rolling Stone provoked me again when it ranked Mitchell 72nd on its 2003 list of the 100 all-time greatest guitarists, two spots below Eddie Van Halen, two above Johnny Winter. It wasn’t that the magazine was dissing her this time. It was just that it’s incomprehensible to me that you could put Joni Mitchell on this list at all. Not because she isn’t a great guitar player — she is — but because her playing is unique. It’s pointless to compare her with others. It’s like trying to rank Thelonious Monk on the all-time piano player list. He’s not “better” or “worse” than Bud Powell. He’s his own species, his own genus. Like the aardvark. Like Joni Mitchell.)

Last fall Mitchell got ranked again. The dating site okcupid.com did a word cloud in which it calculated which terms came up most often among the personal profiles of its users. If you count, you’ll find that she’s 18th on the list of The Stuff Gay People Like, four slots higher than “American Idol,” four lower than “the theater.” I’m not qualified to comment on the validity of that ranking. But I do know that 18th on the list of The Stuff Straight People like is “Burn Notice.” Now I have nothing against “Burn Notice,” but it ain’t no Hissing of Summer Lawns. And anyway, at the end of the day, loving Joni Mitchell is not a gay-or-straight thing. It’s a you-get-it-or-you-don’t thing. And while it’s impossible to conceive of Annette Bening and Mark Ruffalo teaming up in a picture as shrewdly commercial as “The Kids Are All Right” to sing a duet of “In France They Kiss on Main Street,” you’ll never get it if you don’t at least give it a chance.

(A final aside. If my memory is correct — and I’m not saying it is — the first time I saw Joni Mitchell in concert was the night after my grandmother’s funeral in 1974. My Grandma spoke almost no English, she used her hands to make homemade pasta — on a chitarra, no less — and was passing with her generation into history; Joni Mitchell was hyper-literate, she used her hands to form utterly original chord voicings on her detuned guitar, and her generation was just coming into its own. It was, to my very young eyes, a whole new kind of womanhood on display that night.)

When Elvis Costello called The Hissing of Summer Lawns “a misunderstood masterpiece” in the 2004 Vanity Fair piece he wrote about Mitchell, I felt almost thoroughly vindicated. But I still can’t get over that Rolling Stone review, and if I ever meet Stephen Holden, I might challenge him to a duel.

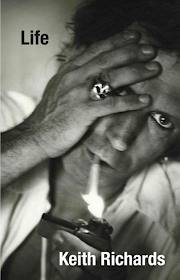

Rock ‘n’ Roll, Drugs and Sex (In That Order)

A review of Keith Richards’ autobiography, “Life.” First published on the PBS Need To Know website in 2011 – given a light edit here

by Tom Casciato

On November 3, 1964, the mayor of Cleveland, Ralph S. Locher, banned the Beatles and what The New York Times called “similar singing groups” from performing at the city’s venerable Public Hall. The mayor’s reasoning: “Such groups do not add to the community’s culture or entertainment.” The ban would go into effect that night, immediately following the appearance of what the Times referred to as “another group of shaggy-haired English singers” — the Rolling Stones.

There’s an easy irony to be had pointing out that Cleveland is now home to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which presumably would treat a 1964-era lock of that hair as a holy relic.

But a more telling irony is found in another Times piece from the era, this one about how musicologists were “astonished” by the popularity of the Beatles and their shaggy ilk. (Back then, it seems, there was very little written about the Stones that didn’t mention the Beatles, too.) In a 1965 piece entitled “Beatles Stump Music Experts Looking for Key to Beatlemania,” The Times noted that “The Stones, as they are called, have a rough, wild style in which everyone seems to go his own way.”

Wrong. What the Stones had was a rough, wild style in which just the opposite occurred – which brings me to “Life,” Keith Richards’ pleasingly anecdotal, breezily amoral memoir that well proves that point, containing generous helpings of Richards’ own brand of musicology to go along with the requisite tales of debauchery and criminality.

In fact,”Life” throws the holy trinity of bad behavior into reverse — proffering rock ‘n’ roll, drugs and sex, in that order. As such, Richards’ recollections have become essential not only for those readers interested in the salacious (who, despite the odd blowjob reference, will be disappointed to learn how often our Keef prefers to just “cuddle”) and the druggy (who will finally discover whether or not he really did have every drop of blood in his body replaced) but also for people who care about the Stones mostly for their records. In fact, what makes “Life” so compelling is that Keith Richards’ love for the music is as pure as the pharmaceutical cocaine he so adores.

There are nuggets galore. One of my favorites: Richards reveals how he managed to create the legendary sound of a song that to this day epitomizes tough-ass rock, “Street Fighting Man,” without using a single electric guitar, save the bass. If that sounds preposterous, put in your earbuds and check it out — those are all acoustic guitars, recorded onto an old Phillips cassette recorder and played back through a speaker into a microphone and laid back to tape to create a rocking, distorted sound, but one quite unlike any an electric guitar would make. Who knew?

There’s also a mini guitar-playing seminar, in which Keith tells how he discovered (via Ry Cooder) the ringing drone that came with tuning his guitar into an open G chord, leading him to explore the neck of the guitar as if finding a whole new instrument, and discovering the signature voicings of some of the Stones’ best-known riffs — the defining guitar parts of “Honky Tonk Women,” “Brown Sugar” and “Start Me Up” among them — and eventually taking the lowest string off his guitar altogether, allowing him to easily finger five-string jangly barre chords that have baffled his would-be imitators ever since. He takes a gleeful poke at the millions of bar bands he’s seen trying to play Stones songs in standard guitar tuning: “It just won’t work, pal.”

But by far the most satisfying bits are those that describe Richards’ love of the innovative styles of his idols — Jimmy Reed, Scottie Moore, John Lee Hooker, Chuck Berry, et al. — and how he and his mates incorporated them into what became the Stones’ signature sound.

Put those earbuds back in and take a listening tour:

He admires how Jimmy Reed and his band were able to transform the repetition, even monotony, of songs like “Baby What You Want Me To Do” and “Take Out Some Insurance” into “this sort of hypnotic, trancelike thing” that greatly influenced the Stones.

He revels in how Elvis Presley’s “Mystery Train” — featuring Moore on lead guitar — is one of the greatest rock ‘n roll tracks ever despite its having no drums. It proves, he says, that a suggestion of rhythm is sometimes all that’s necessary: or in his words, “It’s got nothing to do with rock. It’s to do with roll.”

And he adores John Lee Hooker’s willful disregard of the ordinary time-keeping that causes ordinary blues players to change chords on the beat within a 12-bar structure. (If you really want to hear a performance to baffle the musicologists, try to count along to Hooker and his band romping through this live version of “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer.” You will hurt your head.)

But what he clearly loves most is what he calls “the magic art of guitar weaving,” loosely defined as “what you can do playing guitar with another guy.” But “weaving” isn’t just two guitars playing at once; it’s two guitars in utter sympathy with each other, one countering the other harmonically and rhythmically, creating an appealing architecture that blurs the traditional lines between “lead” and “rhythm” guitar.

His “weaving” heroes include Muddy Waters with his brilliant backup guitarist Jimmy Rogers, The Aces’ Louis Myers with his brother David, and Chuck Berry with himself. (While acknowledging Berry’s studio brilliance, Richards charges that Berry overdubbed “because he was too cheap to hire another guy most of the time.”)

But, of course, if you made a list of the greatest guitar weavers of them all, you’d have to include Keith Richards and whoever he happened to be playing with at the time. Give a fresh listen to the break on 1965’s “The Last Time,” with Brian Jones playing the main riff and Keith layering his part on top. Then there’s Keith — without apologies to Chuck Berry — overdubbing those multiple acoustic guitars on “Street Fighting Man.”

Perhaps the epitome of guitar weaving can be found on 1978’s “Beast of Burden” from Some Girls. The song was a big hit and you’ve heard it a million times. But do yourself a favor and give it a new, close listen where you ignore everything but how Richards and guitarist Ron Wood play off each other. (Keith’s is the first guitar you hear, Wood’s the second, and there are definitely some overdubs as well.) They create the audio illusion (if there can be said to be such a thing) of “everyone going his own way,” but what’s really happening is that the players are finding their way together. The rhythm is the lead, the lead the rhythm, the playing gently slinky, impeccably timed. As such – you’d likely find no disagreement in Cleveland – the community’s culture and entertainment are served.