A legendary guitarist and his story finely — and finally — told …

by Tom Casciato

I saw John Fahey perform only once, at an auditorium at Stanford in, I think, the very early ‘80s. Fahey was a guitarist’s guitarist, and his style of steel-string fingerpicking had a devoted following in Palo Alto, William Ackerman’s local Windham Hill label having recently boosted the genre’s visibility and popularity. The crowd was poised for greatness. Fahey, though, was terrible, and he was drunk. He looked lost in the very place I figured he should have been at home – the stage – and I left the show sad and puzzled.

Fahey was a giant of the solo guitar genre. His first LP Blind Joe Death, was released in 1959 when he was just 20, and though only a hundred copies were pressed originally, it has become a classic. Another landmark record, his 1968 album, The New Possibility, was a collection of impossibly beautiful renditions of traditional Christmas songs that a person – for example, me – might have thought long since hackneyed. But by the time I saw him, Fahey’s position had been usurped by younger players — first Leo Kottke, then, in quick succession, Ackerman and Alex DeGrassi. One after the other they surpassed Fahey in technique and/or speed, and each brought enough soulfulness to the party so as to make Fahey seem pretty close to anachronistic. But if they were the Wilt, Kareem and Shaq of the genre, Fahey was the George Mikan, the one who – as Warren Zevon once said of Bob Dylan — invented the job.

But by the time I saw him, Fahey’s position had been usurped by younger players — first Leo Kottke, then, in quick succession, Ackerman and Alex DeGrassi. One after the other they surpassed Fahey in technique and/or speed, and each brought enough soulfulness to the party so as to make Fahey seem pretty close to anachronistic. But if they were the Wilt, Kareem and Shaq of the genre, Fahey was the George Mikan, the one who – as Warren Zevon once said of Bob Dylan — invented the job.

His playing walked an elegant line. It was gritty enough to a lay a claim to the blues, and never so earnest as to be dismissed as “folkie.” His songs and structures were formal but not pinched. It was music that had connections to the Delta, to ragtime, to Europe and even India, but it couldn’t claim those places as its own. Mostly, it was American music, borrowing, stealing, rearranging and ultimately creating something new. And unlike most of what I grew up listening to in the early 1970s, during the heyday of the singer/songwriter, it had no words.

Though I listened to music (on my crappy stereo) intently as a kid, taking in every voicing of a chord, every slur of a note, every accent of a snare, I was literal-minded enough to take my narrative purely from the lyrics. It was the Beatles, and John Lennon in particular, who first hooked me, with story-songs like “In My Life” and “Norwegian Wood.” I believed him when he said he needed “Help!” When he said of himself “I’m A Loser” I believed him. I knew what his songs were about, because he told me himself.

I didn’t know what Fahey’s songs were “about,” though as someone who devoured album credits as eagerly as I did lyrics, I did grab onto the strangeness of the language I found on his LPs. First, there was that name “Blind Joe Death” – I later learned it was an alias he sometimes used, and now I think of it as a tip of the hat to his bluesman influences (Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ivory Joe Hunter) or perhaps a bit of knowing, Lettermanesque humor decades before David Letterman invented it. (Fahey was more than capable of sidelong wit: one of his early compositions is called “Stomping Tonight On The Pennsylvania/Alabama Border,” comically obliterating the distance between the two states long before the famous James Carville quote did the same.) Back then, I couldn’t figure out what he could possibly be up to.

Then there was the evocative word “Takoma.” That was the name of the record label he owned and recorded on, named for the Maryland neighborhood where he grew up, Takoma Park. I know that now. But when I was listening to Fahey as a kid in Portland, with little knowledge of the country anywhere east of, say, Reno, “Takoma” was a mysterious, somewhat sinister word — a darkened spelling of “Tacoma” perhaps, as “Amerika” was to America? I couldn’t be sure. The music, too, had a mystery to it, as well as, at least for me, a hard-to-grasp kind of pain that unlike, say, Lennon’s, went wholly un-illuminated by lyrics. Whether on a deceptively simple, folk-ish track like “Sligo River Blues,” or the bluesy but deliberate “Some Summer Day,” Fahey played like someone for whom the music was much more than pretty.

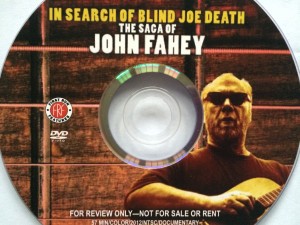

I now know much more about what John Fahey was trying to get across having seen James Cullingham’s fine 2013 documentary, In Search Of Blind Joe Death: The Saga Of John Fahey. It’s a love letter of a movie that gives the master his due, from filmmakers, fans, and fellow musicians (Pete Townsend, Stefan Grossman, Chris Funk of the Decembrists and Calexico’s Joey Burns, among them) who really get what Fahey’s music was about.

The film makes Fahey the person – rather than Fahey the guitarist — appear to have been mostly unknowable. The comments unrelated to his playing are not particularly revealing. But throughout many choice, vintage clips, Fahey manages to make himself known nonetheless. Whether blithely knocking cigarette ash into the soundhole of his Hawaiian guitar (though a solo acoustic player, “the guy was truly punk rock,” Funk observes astutely) or admitting to a violent urge (“I think the guitar helped keep me from going nuts … I could sit around and bang on the guitar instead of banging on somebody else.”), Fahey nearly always displays an edge befitting his beautiful-but-not-sweet style.

But throughout many choice, vintage clips, Fahey manages to make himself known nonetheless. Whether blithely knocking cigarette ash into the soundhole of his Hawaiian guitar (though a solo acoustic player, “the guy was truly punk rock,” Funk observes astutely) or admitting to a violent urge (“I think the guitar helped keep me from going nuts … I could sit around and bang on the guitar instead of banging on somebody else.”), Fahey nearly always displays an edge befitting his beautiful-but-not-sweet style.

The film has more to recommend it as well, including great stock footage of Fahey in performance at various stages of his life. But you also witness him slipping, disheveled, deeply into alcoholism when he moves, in the early ‘80s to Salem, Oregon, an unlikely home for an artist who Pete Townsend compares to William Burroughs and Charles Bukowski. (There’s also – a personal pleasure for me — some vintage 8 mm stuff of Portland, including shots of the classic Hollywood Theater and the kitschy Pagoda restaurant.) Health crises and, eventually, poverty would follow, until he died in 2001.

But it wasn’t until about three quarters through that In Search Of Blind Joe Death supplied what for me are the lyrics of his music, the words that I felt but never heard all those years ago. I won’t spoil it with a direct quote – if you like his music you should see the film — but suffice to say that Fahey sources his pain in abuse he suffered as a child.

His telling is brief (and the film handles it with taste), but hearing it was just enough to send me back to that night, decades ago, when I saw the sorry legend embarrass himself in front of a crowd who had no doubt come to praise and even worship him. It didn’t make the music sound any better in retrospect. But now, decades later, I think I understand what his songs were about.

Or maybe I don’t. I’ve no doubt that the experience of an artist like Fahey shows up in his art, but exactly how remains a mystery — no matter how much I want to pour my interpretation of his feelings into his work. But after seeing In Search of Blind Joe Death, there is one thing I do understand, something that takes me back to that John Fahey show I went to all those years ago. Around the same time, I went to hear Hunter S. Thompson speak at the same auditorium. He, too, was drunk (or stoned, or both, or whatever). Far worse, he was a bore. Fahey, all messed up on that same stage, seemed something else: a tragedy. Now I know why.

Here are a few Fahey favorites, including the tunes mentioned above …